Pineapple Brown Sugar, Federal Donuts - Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

The Uniform Monday Holiday Act is an act of Congress that amended the federal holiday provisions of the Code of Law to establish the observance of particular national holidays on Mondays, rather than their originally designated date. For example, Memorial Day used to be always on May 30, but now it is celebrated as the last Monday in May.

The purpose of this act was to provide federal employees with more three-day-weekends, although as one might ascertain, it wasn't entirely in good faith. The House Report on the Uniform Monday Holiday Act claimed it would "enable Americans to enjoy a wider range of recreational activities, since they would be afforded more time for travel; provide increased opportunities for pilgrimages to the historic sites connected with our holidays, thereby increasing participation in commemoration of historical events; and stimulate greater industrial and commercial production by reducing employee absenteeism and enabling work weeks to be free from interruptions in the form of midweek holidays."

The support was strong in Congress, but the push for this Act came from the tourism industry, specifically the hotel industry lobby and the American Automobile Association. Americans were more likely to go on vacation if they had three days off in a row, rather than one random day in the middle of the week. Sundays, typically the hardest day for hotels to book, suddenly had no vacancy for the entire weekend. During a typical three-day-weekend, AAA estimates about 34 million Americans go on some type of drive for more than an hour. And for those that were unable to travel, three-day weekends became synonymous with massive blowout sales at the local mall--a way to participate in the escapism of vacationing and relaxation without venturing too far from their homes. In a sense, this act took what was considered to be some of the most “American” holidays and somehow made them more American.

If you've been on the Internet this week, you undoubtedly are aware that this Friday, June 7th, is National Donut Day. It is easy to laugh it off as a social media trend—an excuse for “Big Donut” to up their sales counts and provide a Friday boost before a weekend. . It is, of course—but it’s also a true American holiday in every sense of the phrase; a day that one could recognize as our true Memorial Day.

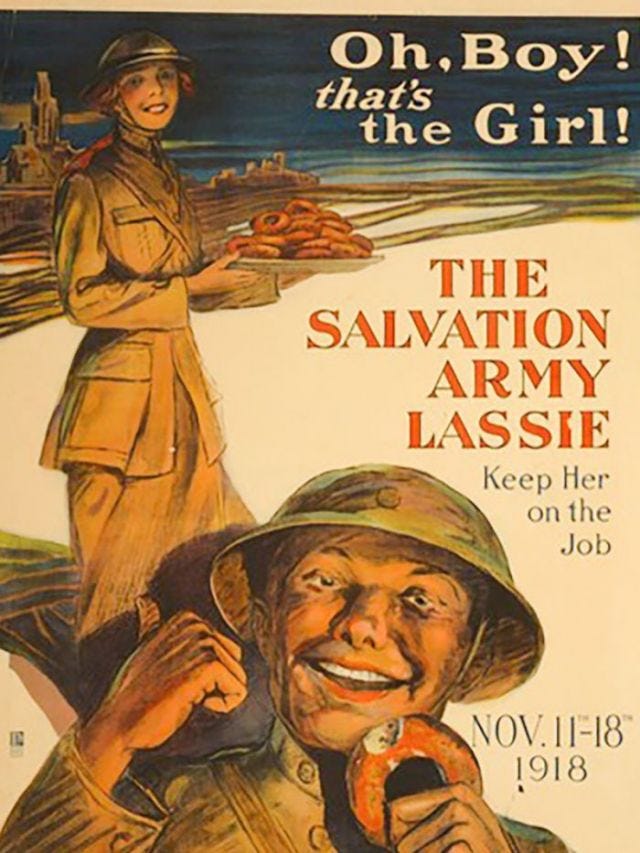

A fact lost to time is that donuts were synonymous with the Salvation Army during the early 1900s, even more so than their incessant bell ringing outside of grocery stores during the holiday season. The women of the Salvation Army who volunteered to help the United States war effort in World War I were tasked with attempting to make the soldiers feel more at home—originally relying upon providing religious services, playing records, and making coffee. Soon, these women, later known as “Donut Lassies,” started making hot and fresh donuts on the front lines: using shell casings as rolling pins and filling soldiers’ helmets with lard to fry the pastries. Some even improved upon the donuts by taking empty condensed milk cans and camphor ice balm tubes to create the ubiquitous donut shape. Ensign Helen Purviance, of the wartime donut effort stated, “I was literally on my knees when those first doughnuts were fried, seven at a time, in a small frypan. There was also a prayer in my heart that somehow this home touch would do more for those who ate the doughnuts than satisfy a physical hunger.”

This is one of the reasons why we regard donuts as distinctly American—propaganda showing American soldiers with a hot cup of coffee and a stack of donuts lanced through a bayonet at the end of a M1917 Enfield rifle. There are stories of American soldiers introducing the donut to our allies; the same way that while in World War II, American soldiers would ask for their espresso diluted with hot water, and similarly, both stories are simultaneously apocryphal and unconfirmed in nature. While the women of the Salvation Army were just as well-known for their apple pie baking skills, “Donut Lassie” stuck, whereas the phrase “as American as donuts,” sadly did not catch on, probably due to an alliterative discord.

If we know anything about this beautiful yet toxic, complex grand experiment of a country of ours is that someone has always gotta be selling something. In this case, the product was enlisting. This was part of Woodrow Wilson’s push to turn the public’s opinion on the European conflict, which had been overwhelmingly in favor of neutrality, toward the belief that this was a just war. The Committee on Public Information created a media blitz—giving journalists an average of ten pieces a day on the war effort, spinning it in a way that favored intervention and encouraging young Americans to volunteer for the war effort. This, coupled with the lack of access many journalists had to the actual frontlines, meant that newspapers were essentially forced to run these pro-war stories, or else they would have no paper at all. The articles included stories of heroic deeds, and of horrible atrocities believed to have been committed by the German people. And, at the forefront, photographs and comics of the Donut Lassies handing out freshly baked cake donuts: five cups flour, two eggs, two cups sugar, five teaspoons baking powder, two cups milk, and a few dashes of salt. The newspapers back home, when reporting on the Salvation Army’s donuts, had a quotation from an anonymous soldier that said, “if this is war, let it continue,” as if the taste of the donut was so heavenly that it was worth spending 30-day stints in the trenches in the Ardennes.

Thus, National Donut Day! Established in 1938 by the Salvation Army to commemorate and celebrate the American effort during World War I, and bring back positive connotations to serving overseas. Franklin D. Roosevelt regarded war with Germany as inevitable, although incredibly unpopular amongst those in the United States, who repeatedly doubled down on their isolationist beliefs. While the United States famously did not officially enter World War II until 1941, attitudes toward Hitler and the conflict in Europe started to change well before then, with the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940. Inevitably, the government turned again to the comfort of the donut of war: not only reintroducing the world to the Salvation Army’s Donut Lassies, but also their bigger and better version: the Red Cross’ Donut Dollies, sporting ruby-red lipstick, knowledge in wound care, and small armament training.

Therefore, it is only fitting that National Donut Day is celebrated during a particularly militaristic time of the summer: those ten days or so that comprise of Memorial Day as well as D-Day, on June 6. Furthermore, the first draft lottery took place during that first week of June, adding to the theme of the week. While listening to Alabama Sports Radio this morning, I heard many callers lament how soft this generation has gotten, and how their grandfathers and fathers went off to war and proudly defended this country, whereas, say, millennials like myself spend their days posting pictures of donuts to Instagram. We like to imagine the American Soldier as the best of us—someone willing to run head first into the Atlantic Wall in hopes of toppling a great evil, though only 38.8% of the American Armed Forces in World War II were volunteers; the military personnel growing from 334,473 in 1939, to 12.2 million by 1945.

Of course, many of these soldiers soon learned that there was no such thing as a free donut.

Literally.

In 1942, after a request from Henry L. Stimson, then Secretary of War, the Red Cross began charging for donuts. British soldiers had to pay for their snacks and coffee, and it was regarded to not be helpful for morale. The Red Cross has since stopped charging for donuts, but for most veterans, this has not been forgotten.

On National Donut Day, there is also no such thing as a free donut. Dunkin’ is offering a free donut with the purchase of a beverage. My local place offers a free glazed donut with the purchase of a dozen. Others require wearing a particular outfit—a pledging of allegiance to the donut in hopes of receiving a free sprinkled of their choosing.

It is hard not to be cynical about the increasing military fetishization of this country—of how war and warmongering is considered to be a positive: of how despite the military being composed of 40% racial and ethnical minorities, our persistent image is that of the white fresh-faced American soldier. Our President is attempting to ban trans people from military service. The rate of suicide among Veterans is 1.6 times higher compared with non-Veterans.

However, I am still susceptible to the narrative of this country and the promise that it holds. I think often of my grandfather, who for most of my young life worked at a military antique shop—of how I collected figurines; wore authentic helmets in pictures. I think of how our country fought fascism and prevented a regime based entirely in hatred from taking over the world. That people gave their lives for this—that many of them would do it again even without the promise of a free donut.

I want so badly to celebrate.

I know that we continue to celebrate National Donut Day on a Friday because that is when we are most susceptible to joy; that there is the promise of the weekend ahead, and all we ever want to do is start it early with a little pick-me-up. It helps us get through the day to the clearer days ahead, and if that’s all that it does, so be it. I know that it wouldn’t have the same effect if it were on, say, a Wednesday. I know that a single donut on Friday means purchasing a dozen donuts for Saturday. I am susceptible to propaganda. Freedom isn’t free.

Instead, let me tell you about a free donut. In September, I was in Philadelphia for 36 hours to officiate the wedding between my friends Cammy and Laura. After going through the ceremony: the queuing of music, the coordination of speeches, the proper way to hoist a chuppah, I had time to kill before meeting friends for lunch. I decided to walk further South to one of my favorite donut places in the country, Federal Donuts. Cammy was one of the first people to take me to Federal Donuts when I was in town for a different wedding a few years prior, and I fell in love with it—they have a great balance between “fancy” and “non-fancy” donuts. As I was on my way to lunch, I picked out a few of their fancier fare: a caramel latte donut, a pineapple brown sugar, and a pumpkin pecan maple. During my time at the counter, I talked briefly with the woman who rang me up—I explained that I was in town for a short period of time for a wedding and that stopping by Federal Donuts was a priority of mine. I ate the pumpkin pecan and the caramel latte, and stored the pineapple brown sugar in my backpack for later—complete with my wedding clothes for later in the evening. On my way out the door, the woman gave me a small paper wrapped present: a still-warm Cinnamon Brown Sugar donut. I happily ate the donut on my walk—the spice blend just enough to not be overpowering; the dough perfectly fried. A donut that would taste just as good while not warm, but the fact it was straight out of the fryer brought it to a much higher level. The walk to find my friends took me through Old City—past the Liberty Bell and the Betsy Ross House, over the cobblestoned streets and shadowed by the Italianate architecture. Here, amongst some of the oldest buildings in the city and the birthplace of our country, I enjoyed the simple kindness of a stranger.

The wedding itself was beautiful—a celebration of queer love with an overabundance of toasts and many small plates with dear friends. For the after party, we all made our way to The Trestle Inn, a Callowhill staple go-go bar that has been a bar since the 1910s. On the dance floor, the brides danced with locals, as I caught up with old friends that had flown in for the wedding. At some point, I remembered the final donut—still in my backpack underneath my formal shoes I had already changed out of. In the dark back room, me, Cammy, and our friends split the donut amongst the flashing lights and soul instrumentals. The acidity from the pineapple hadn't been lost to the baking process, as the strong fruit flavor shined through. The brown sugar glaze was sweet, but not too sweet. It tasted triumphant--all pomp and circumstance. It tasted American. It tasted like home--the best possible imaginable version of it; the home that was never truly delivered but was eternally promised. It tasted like a donut worth fighting for.